Making Sense of the IPF vs USAPL Drug Testing Fiasco

The conflict speaks to a wider issue around drug testing, legitimacy, and the IOC's power over sports.

Competitors and enthusiasts the world over have felt the rumblings of a conflict brewing between two of the most well-recognized and legitimatized powerlifting federations since the dawn of the sport: the International Powerlifting Federation (IPF) and USA Powerlifting (USAPL). The uncertainty of the last couple of years, marked by the pandemic and all of the global restrictions and despair that come with it, has been thickened for American powerlifting athletes by a dispute between the parent and child federations, facilitated via passive-aggressive social media posts and vague press releases.

Most recently, it has transpired in a year-long ban by the IPF of all USAPL lifters. While many athletes have been able to circumvent the ban by competing under US Virgin Islands Powerlifting Federation at the upcoming IPF World Championships, all top-tier US athletes are left wounded in the crossfires of this battle, uncertain about what the future holds. The USAPL has distilled the conflict down into a single blanket statement: that the IPF is banning the USAPL because of “too much testing”. This distillation has inspired much controversy and bike-shed arguments in the powerlifting community, but at its core, it’s the truth, even if the USAPL’s non-compliance might jeopardize the IPF’s standing as a World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) signatory. Rather than enable the USAPL to test as they will at the local level, the IPF would rather see the USAPL reduce overall testing or perform no testing, particularly at the local level where testing is not compliant to the WADA Code, an ordinance put forth by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to guide drug testing in sports. To be clear, the USAPL does adhere to WADA’s Code at national or high-level events and for out-of-meet-testing, but cited a massive increase in costs (third party testing, WADA-approved labs, etc.) associated with implementing the WADA testing across the board necessary to retain the IPF’s status as a WADA signatory.

This moment of time is another chapter in the history of powerlifting’s lifelong struggle to attain legitimacy on the world stage. It’s a moment inextricably linked to the history of the sport itself, the IOC’s power over organized drug-free competition, and the monopolization of drug testing in sport’s, hindering the drug testing movement’s ability to level the playing field and turning it into a political issue.

The History of the IPF Is the History of Modern Powerlifting

To understand how we’ve arrived at this inflection point and for historical reference, we need to understand the history of international powerlifting as a sport, and how anti-doping came to prominence. Powerlifting’s young history and the IPF’s own history are inextricably linked, but the history of drug-free powerlifting starts most prominently with the birth of the USAPL.

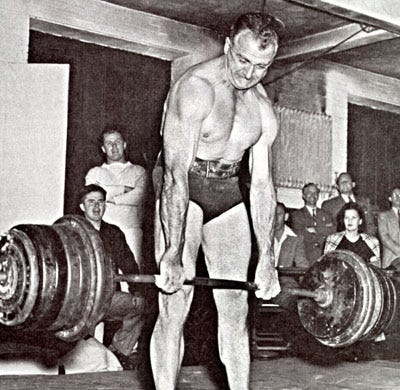

Alongside the emergence of Olympic Weightlifting in the 1900, strongmen and athletes turned towards unsanctioned, unstandardized competitions in what were then known as “odd lifts”, often not so unfamiliar compared to many presses and pulls performed today. By the 1940’s, athletes like Bob Peoples, who deadlifted over 700 pounds at 181 body weight, represented a growing thirst for demonstrations in raw strength, and the 50’s saw a decline in interest for Olympic Weightlifting.

Bob Hoffman, the founder of York Barbell, which at the time was perhaps the most prominent lifting equipment producer, was a proponent of Olympic Weightlifting and initially held disdain for “odd lifts”. However, in short time, he recognized the sea change happening in the industry as people flocked towards bodybuilding and strength movements. In 1964, he organized a Powerlifting Tournament. The next year, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), which was essentially the governing body of all Olympic sports in the US, endorsed an event which selected squat, bench, and deadlift as the main events.

By the late 60’s and early 70’s, cross-national meets were held between French, British, and American athletes. In 1972, following the hosting of a world-level event in Los Angeles, the IPF was immediately established. The AAU would remain the governing body of powerlifting in the United States, until the Amateur Sports Act of 1978 would deplatform them from governance and require unique governing bodies per sport. This would give rise to the United States Powerlifting Federation (USPF).

The early days of powerlifting were marked by a period of experimentation with chemicals, materials, suits, and equipment to try and eke out the most ridiculous numbers feasible. Technologies introduced by early players like Inzer and their ilk, such as the bench shirt and wraps, were just half of the story around performance enhancement; athletes were simultaneously experimenting with drugs. At the same time, the anti-doping movement had just begun picking up steam in tandem with the rise of modern powerlifting, as anabolic steroids were first banned in the Olympics in 1975.

Conflict over drug usage in the sport compelled some people to form splinter federations away from the USPF, including the American Drug Free Powerlifting Association (ADFPA), formed in 1981. A year later, the IPF decided to implement drug testing; thanks to their non-conformity to the IPF’s new stance on doping, the IPF and USPF went their separate paths, and the ADFPA became the new regional federation for the IPF in the states, eventually renaming itself to the USAPL. Eventually, rooted in the same desire to benchmark unaided strength and widen the sport’s appeal, unequipped (“raw”) divisions began to take form in the early 2000’s and surged in popularity until, eventually, it became the predominant and de facto form of powerlifting after being adopted by the USAPL and IPF in 2008 and 2012, respectively.

Evidently, the IPF is no stranger disbanding from their regional subsidiaries when the tides demand it, even in the States, where the member federations wield more power thanks to powerlifting’s popularity here. More than likely, even many of the most hardcore powerlifting aficionados pay no mind to the USPF anymore. So it begs the question; why is the USAPL going to bat over this at the risk of succumbing to irrelevancy? It’s quite simple: the conflict of the early 80’s had to do with the overall direction of the sport and sports in general towards drug-free and eventually raw competition; this modern conflict is over the political aims of the IPF. This hasn’t been a months-long tussle, but a drawn-out, years-long ideological battle over the IPF’s legitimacy on the world stage that has recently begun snowballing out of control.

As far back as 2018, the IPF invalidated 171 doping suspensions whose samples were collected via non-WADA compliant measures and began demanding restructuring of the USAPL’s doping program. It was the first year the IPF had achieved Tier One recognition from WADA, bringing them one step closer to achieving official recognition from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and further cementing Powerlifting and the IPF’s legitimacy. The IPF did not feel it prudent to allow the USAPL to operate and administer drug tests autonomously, as any member federation diverting from the IPF’s allegiance to the WADA Code stood as a threat to their Tier One badge. WADA’s own comment on the matter was additionally perplexing, namely that they had no jurisdiction over national entities.

The USAPL’s qualms with the IPF have amounted to some core tenets, including:

the IPF’s opaque drug testing program (non-disclosure of testing methodologies, schedule, or results, which are not a stipulation of the WADA Code);

the reduction in overall drug testing facilitated by the cost associated with 100% WADA-compliant testing (third party);

lack of requirement for member nations to test, resulting in an uneven playing field.

In 2020, the USAPL administered about 204 out-of-meet-tests, all of which were WADA-compliant, and about 236 WADA-compliant tests in total, out of 1249 total tests and a little over 5000 total competing lifters. It’s difficult to compare against the IPF’s testing practices, because there is virtually nowhere to find publicly available IPF testing data. However, in 2018, the USAPL had a registered testing pool of about 400 versus the IPF’s 29 out of their ~2000 regular international competitors. The IPF themselves have even admitted to cutting testing frequency in the interest of cost cutting.

Because the IPF is requiring member nations to test using only WADA-compliant practices and labs, the USAPL’s argument boils down to the notion that it’ll inevitably become too expensive to test at the same frequency and level that they do now with in-house testing practices. The IPF’s response to this is that they must enforce WADA compliance amongst all member nations if they are to continue to pursue/retain IOC recognition, International World Games Association (IWGA) membership, International University Sports Federation (FISU) membership, and many other multinational groups the IPF deems vital to bolstering the legitimacy and reach of powerlifting. Evidence of enforcement of the USAPL’s adherence to the Code can be found in article 20.3.2 of the WADA Code, apparently recently updated for 2021:

20.3.2 To require, as a condition of membership, that the policies, rules and programs of their National Federations and other members are in compliance with the Code and the International Standards, and to take appropriate action to enforce such compliance; areas of compliance shall include but not be limited to: (i) requiring that their National Federations conduct Testing only under the documented authority of their International Federation and use their National Anti-Doping Organization or other Sample collection authority to collect Samples in compliance with the International Standard for Testing and Investigations; (ii) requiring that their National Federations recognize the authority of the National Anti-Doping Organization in their country in accordance with Article 5.2.1 and assist as appropriate with the National Anti-Doping Organization’s implementation of the national Testing program for their sport; (iii) requiring that their National Federations analyze all Samples collected using a WADA-accredited or WADA-approved laboratory in accordance with Article 6.1; and (iv) requiring that any national level anti-doping rule violation cases discovered by their National Federations are adjudicated by an Operationally Independent hearing panel in accordance with Article 8.1 and the International Standard for Results Management.

WADA and the IOC Have Too Much Power

In this debacle, there is no quantifiably “right” position. The IPF’s aim has been and always will be bolstering and legitimizing powerlifting on the world stage. The USAPL’s aim since its inception has been to level the playing field and provide the premier drug-free powerlifting experience. The IPF is willing to enforce WADA compliance at the expense of drug testing frequency. If the IPF’s prerogative is incompatible with the USAPL’s motives and vice versa, they may be compelled to go their separate ways.

It makes less sense the more you think on it. Why does aligning with an organization and a code supposedly dedicated to drug-free sport make drug testing more difficult, more costly, and less effective as a result? Why is WADA/the IOC a monopolistic gatekeeper in this equation? Why does it have to be this way?

In essence, it is because of the ineffectiveness, corruption, and power that WADA and the IOC yield over sport. What may appear to be an international body and standard to ensure fair competition across sports, nations, and entities has become a powerful, corrupt gatekeeper.

WADA’s history since its inception in 1999 is marked by a series of corrupt misdeeds and outright failures. Its overall inefficacy would be laughable if it weren’t so sad. In 2017, a WADA-commissioned survey found that 57% of elite competitors admitted to PED usage, compared to a test positivity rate under 4%. As detailed in the 2016 McClaren report which resulted in Russia’s suspension from the Olympics, WADA had, on multiple occasions, deliberately turned a blind eye even to the blatant admission of cheating by the athletes themselves. The IOC as a whole has a long history of incredible corruption, including the acceptance of bribes and, more relevantly, turning a blind eye to drug usage.

The IOC’s application of their own anti-doping code and practices could be described as lax at best and downright corrupt at worst. They themselves even encouraged the IPF to reduce the frequency of tests. It begs the question, then, why subsidiaries and signatories are to be held to such stringent scrutiny and adherence to the IOC’s standards. The USAPL and IPF conflict is, at its core, an ideological conflict set to the backdrop of the IOC’s monopolistic control of drug testing. If the ramifications for non-adherence to the WADA Code were not so tremendous and far-reaching, this would be a non-issue. Unfortunately, the IPF’s aim to be a global hegemon over powerlifting includes working with WADA-adhering international organizations, which is ironically incompatible with the USAPL’s pursuit to create an even playing field.

Perhaps it is in the best interest of both parties to permanently part ways, and sooner rather than later so as to minimize collateral damage to everyone else, such as the lifters, coaches, and the IPF’s potential new member federation. Fragmentation and rules could make it too difficult to compete regularly across federations, and the USAPL could go by the wayside like the USPF before it as a result. But I don’t find that likely; powerlifting is much bigger and coherent today than it was in those days. The USAPL is looking to pursue even more grandiose events with even greater cash prizes in the form of its Pro Series. A world may exist where the USAPL and IPF can coexist without being affiliates, and lifters can compete across both, similarly to the relationship between the NBA and the Olympics. This may not be the end-of-an-era, but the beginning of a new chapter in powerlifting. We’ll simply have to wait and see where the cards fall.

The IPF has move with the IOC to be a "drug tested" organization, NOT a "drug free" organization. This ironic because this is the same approach that USPA was booted from IPF for. USAPL (which is the old ADFPF) will remain relevant as long as they stick to their drug free roots. I would love to see a new version of the WDFPF also. Drug free is a mind set that must be instilled at the local level. WADA "certification "should be required ant the international level. But preventing cost effective testing at the local level is not in the spirit of DRUG FREE lifting.

I mean whats going to happen going forward after this one year ban. It’s not likely for the usapl to change their ways just them holding the new event pro series its a sign for them to be doing their own thing.

The lifters are the one who will suffer those that want to compete at worlds and such but we shall see what happens after this year if the usapl opts out totally from the ipf