Making the Cut

After experiencing and refining my competition water cut process over the years, here are my formulated thoughts and strategies about what works and what doesn't.

Full Disclosure: I am not a physician, and this is not a precise protocol. These are simply recommendations based on my personal experiences and some evidence collection. Any example metrics provided are just that. Risks include but are not limited to hypo/hypernatremia, irregular bowel movements, and heat stroke. See a medical professional if you have concerns or preexisting conditions.

Weight cuts and manipulation have long stood as a competitive strategy in all weight-class oriented sports. The allure is simple: walk around on a regular basis at a much higher bodyweight before rapidly dropping the weight at the last moment. Between weigh-in and the competition, you can refuel to try and make up the difference.

On the surface, it sounds like an obvious way to gain an edge over your competition, but it can have serious implications if done poorly, especially in quantitative strength sports. Currently, it is a bit of an under-researched domain, and the practices surrounding it are a bit of a soft science. As such, people have been relegated largely to pseudoscientific approaches shared by word-of-mouth.

Over the years, I have implemented weight cuts several times while competing in powerlifting with varying degrees of success; some quite large (~5% bodyweight) and some quite small (~1%), all with 24-hours between weigh-ins and the meet. Just this last weekend, I was able to put up a PR total while dropping around 11 pounds over the course of the previous week. Here are some of the lessons I’ve gleaned and the ways I’ve refined my strategy over the years.

Prioritize Losing Fat First

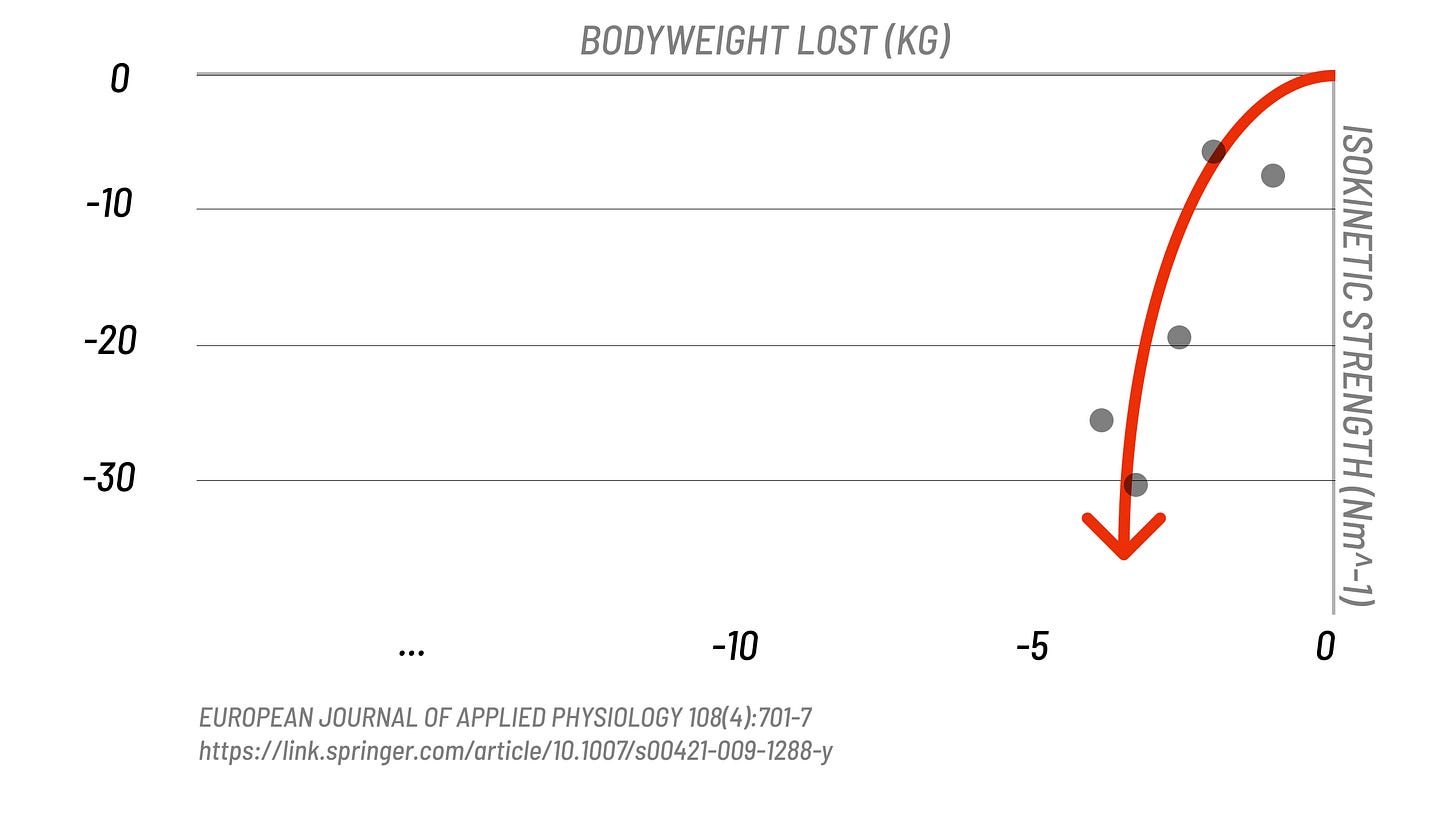

One of the draws of a short-term weight loss strategy is that it enables you to eat at least at maintenance intake through the lead up to the competition. While this is ideal for maintaining strength and performance, you have to be realistic with yourself; you likely aren’t going to lose 10+% of your weight in a single week or two without a significant impact to your performance (assuming no drug usage). There is an exponential relationship between every pound you need to lose via dehydration and the impact on strength performance. That being said, a rapid drop in weight amounting to 5% has been shown to be ameliorated within 12 hours without significant strength consequences, so if you are seeking to perform a dramatic weight cut for a 24-hour weigh-in, I wouldn’t recommend you take it much further than 5%.

Now, the following advice is highly variable between people and is contingent on your starting point. Insulin sensitivity, leverages, training history, and PED usage all play roles here. While I cannot give you a precise minimum body fat percentage to target, you ideally would be as lean as possible while striving to preserve hormonal balance, daily energy expenditure/BMR, and leverages, relative to your baseline. The more experienced you are, the less body fat you will be able to lose without impacting your performance negatively.

For myself, the sweet spot is around 12% body fat, while I generally work up to 15-20% during off-season. However, an experienced super-heavyweight walking around at 25-30+% body fat would have a much harder time staying near peak performance while dropping to 12%.

In other words, if you are between 15 and 30% body fat, expect to be able to drop 5-10 points off that number via a sound diet (20-25% calorie deficit + adequate (~1g/lb. bodyweight) protein intake) before noticing a significant impact on strength. If you can get under your target weight without manipulating food or water, this is ideal.

Forced Dehydration Is the Last Resort, Not the First Priority

When assessing short-term weight loss solutions, forcing dehydration by means of active or passive sweating should be seen as a last resort, not the first step. Oddly enough and contrary to my opinion, many people simply wait-and-see until a few days remain and then decide to hit the sauna or an epsom salt bath. The heat required to induce passive sweating has potentially detrimental effects on strength and endurance and can even be dangerous at presumably already low levels of hydration. You can generally get away with 3-5% weight loss by simply manipulating water, electrolytes, and diet.

In the order of most-to-least desirable strategies, here are how I personally rate them in terms of cost-benefit analysis (numbers 5 and 6 are truly reserved for 24-hour weigh-ins):

16-hour fast before weigh-ins (may need to shorten that window for 2-hour weigh-ins or extend it for 24-hour weigh-ins if you are a bit behind);

Switching to low-residue foods a few days out (avoiding fiber and opting for calorically-dense options);

Loading water throughout the week and cutting it the day before weigh-ins (I work up from 100 ml/kg bodyweight to 120 ml/kg bodyweight);

Loading sodium throughout the week and cutting it up to a couple of days before weigh-ins (my high sodium days target around 4000-5000 mg, while my low sodium days are around 500 mg. If you are a lighter person, you could get away with lowering the high days a bit);

Reducing carbs (I prefer gradually) over the course of the week to lower glycogen levels (I work down to 30-50 grams per day);

As an absolute last resort, the night before or the morning of weigh-ins, induce sweating by sauna, light cardio, jacuzzi, etc.

Have a Well-Considered Refeed Strategy

Depending on which of the aforementioned protocols you might’ve implemented, you will need to have a viable refeed strategy to correct any imbalances or depletions you may have incurred.

Fat intake should not exceed more than is necessary; for simplicity’s sake, this would roughly be in the domain of 0.2 - 0.4 grams-per-pound of total body weight. The majority of your calories should come from carbohydrates, and a significant portion of that should come from high-glycemic, low fiber sources so as to digest quickly. This is especially important if you reduced carb intake as a mechanism to drop water weight. Total glycogen storage is in the ballpark of 15 grams per kilogram of body weight. To replenish this energy, you should at least seek to consume 10 grams-per-kilogram of fat-free mass (i.e., if you are 90 kg at 10% body fat, you should shoot for 810 grams of carbs in 24 hours). You would not be in a primed state to replenish glycogen since you are relatively untrained and depleted, so you should be aiming to ingest this at a rate of around 1 gram-per-kilogram of bodyweight per hour.

On the liquid front, as opposed to chugging them as quickly as possible, you should try to consume them slowly over the course of several hours so as to appropriately absorb electrolytes and water rather than flushing everything through your kidneys. Initially it is probably fine to down some liquid, especially if you are extremely dehydrated, but beyond your initial chug, you should take your time and consume around 1 liter over the course of an hour to properly give yourself time to absorb the electrolytes. I prefer a combination of water, Pedialyte (electrolytes), Gatorade or some other sports drink (also electrolytes), and whey or other liquid protein (to aid in the process of glycolysis). You may also consider something like Clamato or pickle juice if you have manipulated sodium intake and can’t seem to recuperate enough from the aforementioned drinks.

Honorable Mentions

Here are several other factors to consider that perhaps I didn’t have enough information to elaborate on at length, but felt deserved to be included:

Don’t taper the water load down; cut it quickly. You may taper the load up, but cut the water quickly on the last day, maybe the last 2 days at most. You don’t want to give your body any time to acclimate to the reduced intake and impact the diuretic hormones responsible for dropping the water (vasopressin, aldosterone, and ADH).

The same goes for sodium. If you are manipulating sodium, try and wait until the last day or 2 to reduce your intake, for the reasons mentioned above.

Taper carbs down if necessary. Unlike sodium and water, there is no drastic effect to cutting carbs. You may find it necessary to taper your carbs throughout the week to avoid experiencing “keto flu” and other side effects.

Keep track of your morning and night weight on a regular basis. You’ll want to have some sense about how much weight you drop every night. Having access to a calibrated scale is even better so that you have a high degree of confidence in your measurements and their consistency (also, this is generally what they use at competition weigh-ins).

Reduce or eliminate all unnecessary sources of stress during this process. This can be a highly stressful process, especially on the final day. You’ll want to reduce all forms of physiological and mental stress to the best of your ability. Dial-in sleep, avoid drinking alcohol, and rest as much as possible.

Don’t stretch this out. The bulk of this process should only take 5 or 6 days. You don’t want to spend 2 to 3 weeks drinking inordinate amounts of water or eating a paltry few grams of carbs.

Temper your expectations. No matter what your recovery looks like, there is a strong chance that you are still not going to be 100% on the day of competition. Be realistic about the process and be willing to make adjustments and compromises.

Implement only what is necessary. This will require some trial and error over time and knowledge of your own response sensitivity to the various protocols. Of the processes mentioned in the previous section, it’s safe to assume that implementing all of them full-force would probably drop 6-8% of your bodyweight. In which case, for example, if you only needed to drop 3% of your bodyweight, you could perhaps scale back the water load, or skip the low carb protocol.

Honestly, It’s Probably Not Worth It

All of that was to say, you’re probably better off competing at your usual morning weight, or at least close enough (within 1-2% of it) such that losing a few pounds the day prior is not an excruciating experience. I know, I know; you’ve heard it all before, and you’ve already made up your mind. Rather than repeat the same spiel about “not being worth it unless you are competing (inter)nationally or setting a record,” allow me to impart a different perspective.

This last weight cut of mine was perhaps my best-executed drastic weight cut. It was not for a national event or a record, but for a local meet. I lost about 5% of my weight over the course of 6 days. My best lifts in training were conservative; I definitely had left a lot in the tank and expected to show out at the meet. Despite everything being dialed in very well, thanks to a combination of unforeseen judging, the effects of the cut on my squat, and an all-out failed deadlift attempt that I was simply too fatigued to pull off, I couldn’t even match those conservative maxes in competition. Squats were a dizzying experience. I did not feel fully recovered until around the middle of the meet, about 30 hours after I began eating again.

Had I simply weighed in at 94 kg and totaled ~720+ kg as was indicated by training, my DOTS (a standard measuring relative strength) would have been ~455 points. Instead, I totaled 695 at 90 kg and my DOTS was ~450. I won second in my class in the open age category. I believe, even with the 695 total, I would’ve won first in the weight class up from mine (this would be far less likely to occur at a national-level or invitation-only meet, where the relationship between weight and strength is generally linear). I still would’ve won best junior lifter, regardless. In other words, cutting weight had no positive impact on my standing. If anything, it negatively impacted my standing.

While I don’t necessarily regret the water cut, in hindsight, it was superfluous. I would’ve been satisfied to simply compete at my usual weight, perform a little bit better, and perhaps even place higher than I did. Additionally, I could’ve foregone the entire very stressful process of weight manipulation.

For 99.99% of us, the goal of competing should be to enjoy the process, benchmark ourselves, and push ourselves to raise our own personal bar. It should be fun. If rapid, giant weight cuts turn a sport into a miserable and hellish experience, then they are for naught. You may feel compelled to cut weight by some psychological burden bearing its weight on you, whether it be commitment, your own expectations, or something else, and while I can advise you, I can’t change your mind.

But consider an alternative world where you have the leisure to fill out your weight class, to eat mostly as you please, and to not have to induce unnatural weight swings through a vicious cycle of gorging and depriving. I have seen both worlds, and I can tell you right now that you will generally be happier in a reality without weight cuts.