There Is No Such Thing as a Perfect Deadlift

Hips too high? Too low? Too much spinal flexion? Extension? When is perfect the enemy of good?

Deadlifts, one of the staple, big-3 powerlifting movements, are performed by gym-goers all the world over. Even beyond its presence in powerlifting, its applicability in strength training, muscle building, and even the rehabilitation of lower back pain have made it a facet of many competent lifting programs.

On its face, it seems to be one of the most intuitive lifts you can perform. Pick it up, and then return it to the ground. Sure, there are myriad variations, from sumo to Romanian, but the basic premise still holds.

Contrary to the movement’s seemingly black-and-white nature, you may have been bewildered to find that there are plenty of conflicting accounts and opinions of what is “right” and “wrong” when it comes to the deadlift, from how high your hips should be, to which variation to select, to what is an acceptable amount of back flexion. In reality, as with many adjacent concepts, “it depends,” and what satisfies “perfect” for any of these variables won’t look the same for everyone.

Anatomical Variations Will Dictate Setup

As I have discussed in a previous article, anatomy is often a strong influencer of how various compound movements will come together for different people. Particularly, the deadlift will be dictated by the relationship between the relative lengths of your arms, torso, and femurs. Assuming a consistent setup, someone with a longer torso and arms may appear to sit lower, while someone with shorter torso and arms will appear to sit higher, further back, and have a back angle closer to parallel to the ground. Neither position is inherently more injurious or dangerous; it’s dependent on the lifter’s own anthropology.

In terms of strength, the important optimization here is not how high or how low your hips are, but how short the moment arm, or the distance between the bar and your hips, can be, while also finding which joint angle (more simply, conventional or sumo) is optimal for force production for you, as different joint angles leverage different hip muscles. When the total range of motion is consistent, this is the variable you want to effect in order to be as strong as possible.

Even amongst individuals, there seems to be little consequence in variable hip height, depending on how close or far one sets up from the bar. One study sought to compare exactly that. The researchers had the participants set up in 2 different fashions: further from the bar (so as to have to sink the hips lower to bring the shins to the bar) and closer to the bar. They found that the force generated off the floor was consistent when lifters implemented either style. EMG amplitudes measured higher hamstring activation in the close setup and higher quad activation in the further setup, as expected by the level of knee and hip extension involved in either setup. There were no differences in shear or compressive spinal forces, indicating that neither was inherently more dangerous than the other.

That is not to say that one is more optimal for max deadlift strength than the other, as remember, sitting further back from the bar is almost certain to mean your hips have to move a greater distance to bring themselves into the bar, but that neither is particularly dangerous and both are legitimate depending on one’s own training goals.

Some Back Rounding is OK…Sometimes

Addressing back rounding in the deadlift is not as cut-and-dry as some would make it out to be. In some circumstances, it is okay or even inescapable. The key modifier here is “some”; if your back rounding is:

within a tolerable threshold, or;

mostly in the thoracic region;

then it’s probably not cause for concern.

Threshold

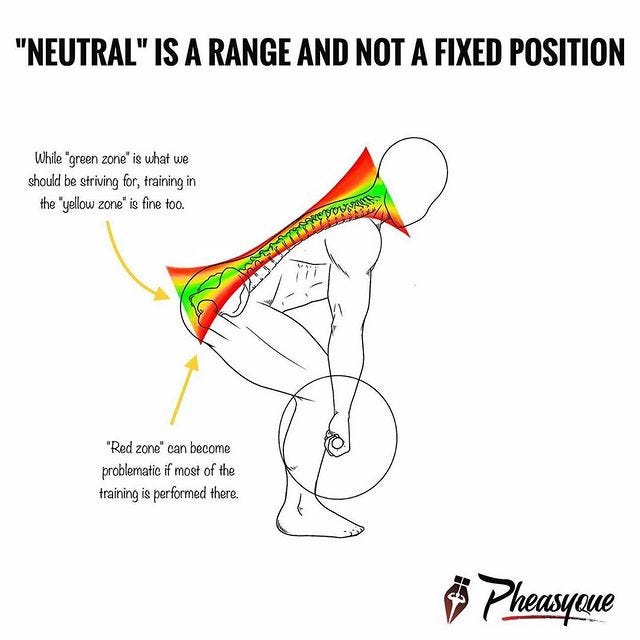

Practitioners often advocate for trainees to assume a “neutral” spinal position when loading the spine via heavy compound movements. It is often portrayed as a relatively flat spine with a natural, slightly lordotic curve towards the bottom. Some would view any deviation from such as sacrilege. While you may or may not be able to satisfy the textbook-definition appearance of “neutrality”, it should not be considered as one singular, rigid representation and should instead be considered across a range of acceptable levels of flexion or extension. This post by Dr. Stefani Cohen does a good job of illustrating this point:

Once you begin to consider all variables, including the lifter’s genetics, baseline spinal positioning, and overall anthropology, the waters become especially murky. For instance, a taller lifter with poor leverages or a more kyphotic spine may be incapable or have a harder time assuming a position that appears neutral. That is not to say that you should deliberately be lazy or sloppy; if getting into the right position is a matter of cues or practice for you, or you are missing a fundamental component of the movement (bracing, for instance), then you should work towards being consistently neutral to the best of your ability. However, if a lifter is consistent from their start position to their lockout, the degree of flexion is extremely minor or very little time is spent in a state of flexion, and the positioning has been tried and tested through time without injury, it’s probably little to worry over. If you are particularly concerned about lumbar (lower back) flexion, I’d recommend this article over by the folks at Stronger by Science, which goes into significant detail around injury risk and the subject of “neutral range”.

Thoracic Rounding

Thoracic rounding, or upper-back rounding, is a technique often leveraged by advanced powerlifters. Technically savvy powerlifters who have the motor ability to let their shoulders sag whilst maintaining lumbar rigidity can shave an inch or two off of the moment arm of their deadlift (bring their hips a bit closer to the bar) in order to be a just a bit stronger without significant risk of injury. You are effectively shortening your torso and, thus, bringing the bar closer to your hips. Powerlifter Richard Cho is a strong advocate of this technique:

Implementing this technique usually requires a great degree of proficiency with the deadlift and a strong sense of motor control in the upper back. A novice deadlifter is unlikely to see a significant benefit from implementing this, especially considering the work likely required to do it appropriately. Still, it’s worth noting that it is generally not a problem so long as the lifter is rigid through the lats and lower back, bracing correctly, and consistent throughout the movement.

There Is No Best Variation

Each of the variations has their draws and failings. In the context of powerlifting-legal variations, the sumo deadlift tends to be a bit more quad-dominant than the conventional thanks to the outward knee travel and upright positioning. Beyond the context of those two movements, there are a variety of alterations, such as the Romanian (RDL), stiff-legged, and others. You will have to be wise about selecting the proper variations conducive to your strength and muscle building goals, and will almost certainly include multiple in your own programming.

Explicitly in the context of powerlifting, contrary to what raging Internet trolls would have you believe, the advantages to either sumo or conventional are not so cut-and-dry; sumo isn’t a +100 lbs. cheat code for everybody. In one study, inexperienced deadlifters who were otherwise well-trained took on testing their sumo and conventional deadlifts. Across the board, there was little difference in 1 rep max strength, 60% AMRAP strength, and no clear anatomical indicators of which would be stronger. Even at the elite level, there are several powerlifters whose conventional deadlift is within spitting distance of their sumo. Yangsu Ren (sumo and conventional), Dan Green (sumo and conventional), and Ashton Rouska (sumo and conventional) are all good examples of extremely strong athletes whose sumo and conventional deadlifts are fairly interchangeable.

That is to say that these findings are not necessarily indicative of long-term training outcomes for everybody, especially because skill acquisition is an important part of sumo deadlifting. If your goal is to lift as much weight as possible, my recommendation is to start prioritizing what comes most naturally and feels most comfortable initially. For most people, this would be conventional thanks to sumo’s skill acquisition curve. You can train them in tandem and alternate priority across several training cycles until you ultimately land on which is stronger. Having a second opinion from an experienced coach is also helpful to ensure you are maximizing either variation effectively.

Don’t make perfect the enemy of good. Your version of perfect may not look like a textbook characterization of the deadlift. You should strive to address fundamental failings and seek to address recurring injuries and blatant weaknesses, but a Yury Belkin upright sumo deadlift or completely balanced hip positioning on the conventional deadlift may not be in the cards for you.

In my own several years of training as a self-proclaimed deadlift specialist, my deadlift has taken many shapes through numerous variations, setups, and technical cues. Despite being far from optimal on multiple occasions, the only time I’ve incurred an injury through deadlifting was a hip injury, and it was the result of inappropriate load management (too much in too little time). I still consider my deadlift a work-in-progress.

The greatest advice I could offer you is to record and analyze regularly, perhaps with a second opinion in the form of a coach or training partner. As with myself and many successful deadlifters, it will take careful experimentation over time to find what works and what doesn’t work for you, so don’t fret if things are not falling into place right away.