What Hidilyn Diaz’s Inspiring Olympic Story Tells Us About Muscle Memory

Despite lockdown measures and unpredictable training circumstances, the elite star still managed to prep quickly and come out at the top of her class. Here's how.

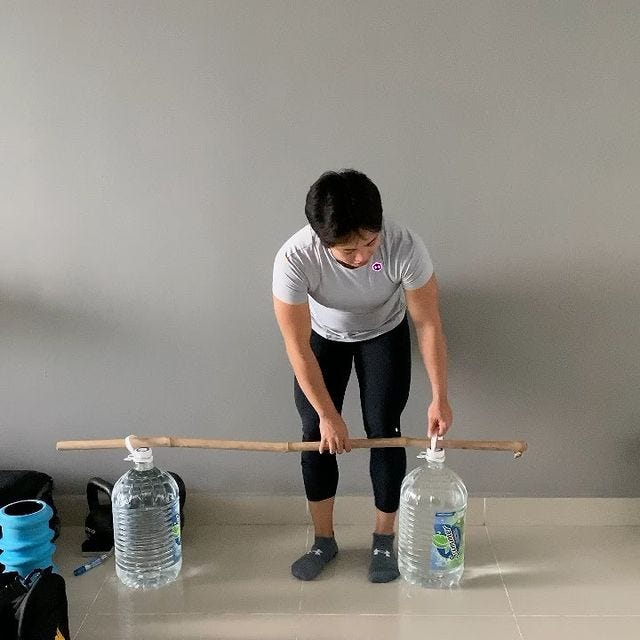

When 30-year-old Hidilyn Diaz trumped her competition and set all-time records in weightlifting during the 2020 Tokyo Olympics this July, you’d had never known that she’d been relegated to far-from-ideal training circumstances. From training with a MacGyver’d bamboo machination, scantily fastened with bands and bottles, to winning on the highest stage in weightlifting, her story clearly imbues inspiration in the hearts of athletes all-over.

It was a victory over 15 years in the making since her first competition in 2006. After ending the Philippines’ 20-year-long medal drought in 2016 with a second place win, she had her sights focused on bringing home the gold in 2020, a first for the Philippines. However, the pandemic loomed large over the world. She was no exception, stranded by travel restrictions in Malaysia from February 2020 right up until the Olympics this July. By April of 2020, the Malaysian Government’s lockdown mandates had closed access to gyms. For nearly 6 months, she was stuck improvising with sticks and bottles until she was able to relocate to a weightlifting official’s home in the coastal state of Malacca. Though she eventually gained access to proper equipment, COVID-19 restrictions forced her outside to train in the sweltering heat, right up until the culmination of her hard work took form as a 224 kg. total in Tokyo.

While rebounding so triumphantly from a months-long period of relative detraining may strike awe (and to her credit, she went to great lengths to optimize her training as best she could), many experienced lifters who’d taken absence from training for any extended period of time (maybe because of an injury, shuffling life’s priorities, or even COVID-19) would have experienced a similar phenomenon of rapid reacclimatization, often referred to as “muscle memory”. The notion that you can much more quickly regain lost muscle and strength compared to when you first built it has long stood as accepted postulate among experienced lifters. This mechanism is what enabled Hidilyn Diaz to emerge from months of subpar training and secure a win in under a year. Only relatively recently have the mechanisms by which these processes occur been explored; namely, gene expression and the retention of myonuclei.

Gene Expression

Recent research seeking answers to the muscle memory conundrum analyzed a process known as gene methylation. Gene methylation is the binding of a chemical known as a methyl with DNA. In simple terms, if DNA are the instructions to be transcribed and translated by various RNA to produce the proteins involved in carrying out biological functions, think of methyls as a stop sign in these circumstances. This process exists because all DNA in the body is the same, but not every cell needs to carry out or express every gene in order to accomplish its functions; hence, methylation. Generally, the higher the level of gene methylation, the less frequently or intensely that gene can be expressed. The inverse is also true.

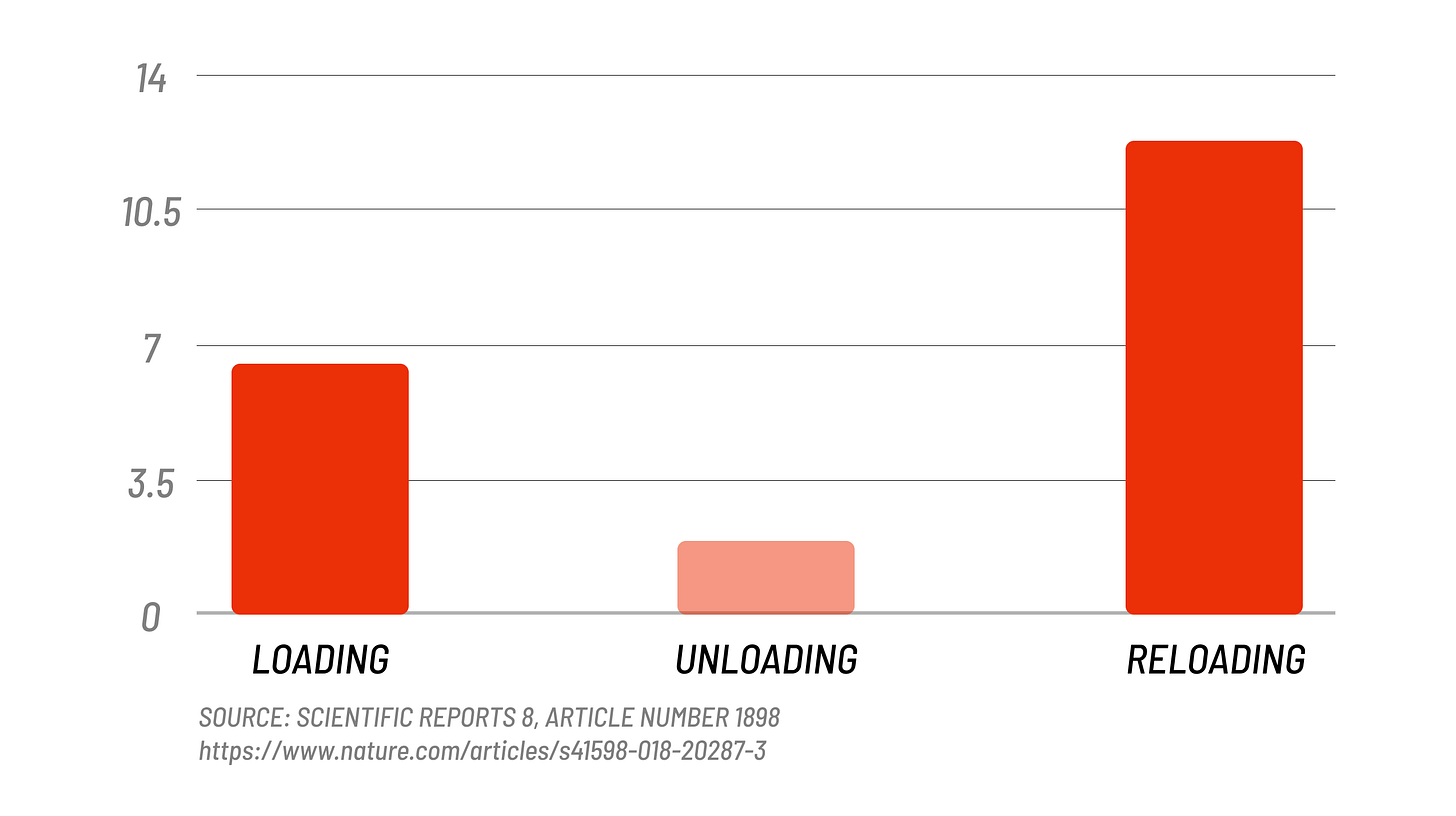

Researchers had untrained, healthy subjects train for 7 weeks, pause training for 7 weeks, and then retrain on the same program for 7 more weeks. Strength and lean mass fell significantly on average during the unloading phase, and then quickly soared past their previous peaks during the reloading phase, indicating that subjects were able to match their previous records quickly.

During all three phases, the researchers analyzed gene methylation patterns, and found that genes directly responsible for growth, hypotrophy, and other processes tangential to muscle building retained lower levels of methylation through detraining (meaning, they’d more readily be expressed). Thus, it can be interpreted that gene expression played some role in bringing their gains back from the dead.

Myonuclei Retention

The scientific consensus on this phenomenon, however, is muddied by the role of another variable: namely, myonuclei. For quite some time, myonuclei retention was believed to be the primary dictate in explaining muscle memory. However, with the advent of more recent research attempting to analyze this idea in humans over longer periods, it’s not entirely clear that the theory holds weight; most likely, this is a variable, but not the principal cause.

Essentially, the idea reads something like this: skeletal muscle fibers, some of the longest cells in the body, are multi-nucleus cells. These nuclei, referred to as myonuclei, are generated by satellite cells on top of the myofibers in response to hormonal or training stimuli. It was originally believed that these myonuclei would persist after muscle has atrophied, but new research has discredited that idea; they simply appear to atrophy at a much slower pace than the muscle itself. Other research, however, has given rise to the idea that the myonuclear domains (the cytoplasm and organelles around those nuclei) are retained with time and may facilitate faster rebuilding of new myonuclei following a period of detraining.

Regardless of how muscle memory is accomplished physiologically, its effects have been documented in science for a long time, and there are likely hundreds of thousands of anecdotal accounts to support the idea. Hidilyn Diaz’s story is a demonstration of the potential for training experience and years of hard work to persist, even at the world-class, elite level and with months-long bouts away from the usual equipment and training. It’s a testament to the veracity of the concept of muscle memory. She made the most of an uncertain situation, retrained her way out of a months-long hiatus, and found a way to show up and show out on the day of reckoning; an example we could all strive to emulate.